University Rover Challenge

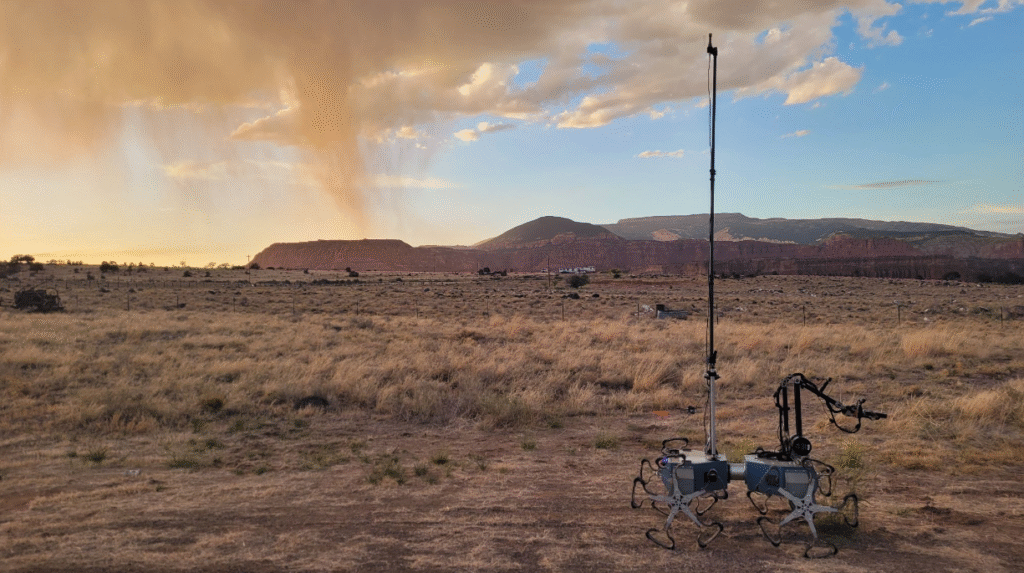

University Rover Challenge is a global collegiate robotics competition located at the Mars Desert Research Station in Hanksville, Utah. Students design rovers to complete various missions each year, and must solve logistical and managerial challenges associated with transporting a robot across the country, in addition to making a competitive robot. Teams qualify for the competition through a 5-minute video submission, pitching the rover’s capabilities and the team’s readiness for the competition.

Among other things, I was the director for Team Mountaineers’ 2025 SAR submission. Watch it below!

At the beginning

I’ve been a member and coordinator on the WVU University Rover Challenge team since my freshman year. At that time, it was just after COVID and the team had been in a rebuilding phase. I was co-leading the Mechanical/Drivetrain subteam. However, since the team itself is a capstone project, this meant that I was leading seniors at the end of their courses as someone who had yet to finish a single course.

At the URC 2023 Competition – When taking this picture, we knew we had won the competition after having an incredible run in our last mission. Sure enough, we got the trophy that night.

So, I adapted my leadership style appropriately. To manage people who knew more about the subject than me, I played the role of an enabler: communicating between sub-teams to manage collaboration and time management, organizing resources and staying on top of shipping orders, and maintaining a cohesive vision such that each person’s individual contributions could come together at the end.

In the first year, we didn’t qualify for the competition. The following year, however, I led my subteam to create new composite wheels- created in-house- that reduced our rover weight by 20% over the 3D-printed TPU tires we had been using.

This allowed the rover to distribute weight elsewhere, and our design qualified for the 2023 competition.

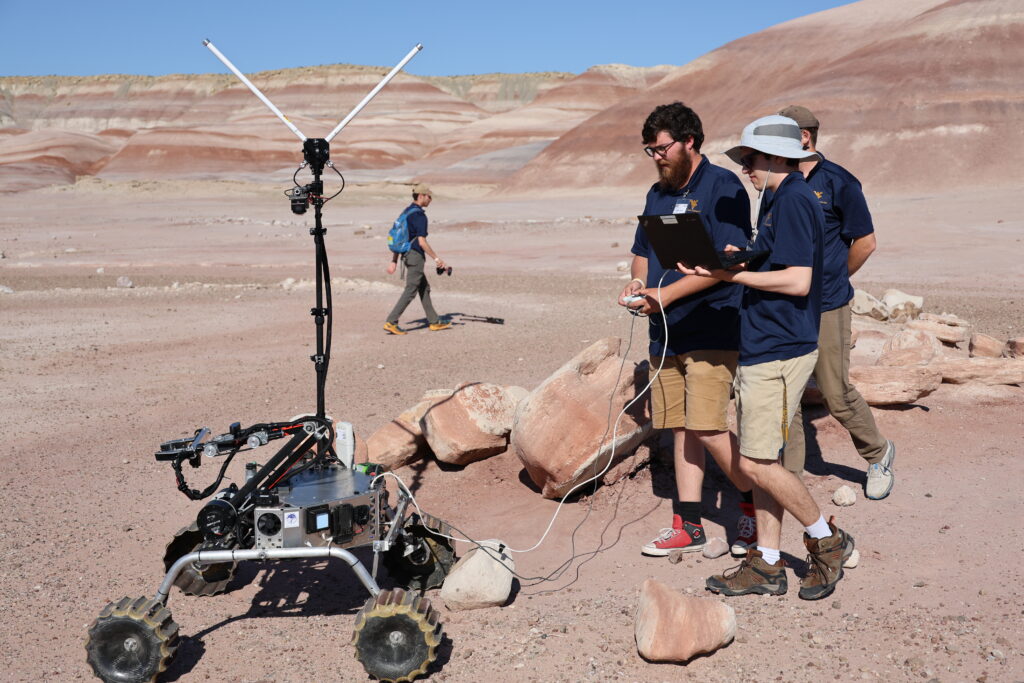

Malik, Riley, and I are presenting the findings from the Science mission to the judges

As one of the 11 team members selected to represent the team in Utah, I found a niche to assist the team by studying geology. Since missions like these can have sudden, unexpected elements to them, the competition organizers introduce new competition elements prior to or at the competition. In 2023, this meant that we needed to identify rocks during the Science mission and put them into the context- what does it mean about the geology of the local area- in a presentation assembled within 10 minutes after the mission ends.

We had a perfect score on the geology section. That was rare that year, due to a particularly tricky piece of limestone that looked like igneous were it not for characteristic white pockmarks.

Oh, and we also won the competition.

Not just luck

Our first year of competition was filled with small misinterpretations and lacked the right perspective that could only be found once at the competition and seeing what the judges were looking for. We were only able to win in our second year due to learning the lessons of the first year and getting the right perspective. To mitigate this effect for other teams, we open-sourced our winning robot and its code for all teams to use.

We also collaborated with another team, Monash NOVA from Australia, to write an engineering article about the two different logistic approaches to the challenge each team took. You can read the article here.

For myself, after experiencing the Science mission and seeing a significant gap in the team regarding the development of the Science payload, I decided to switch to coordinating the Science sub-team for the upcoming year.

Now having more experience under my belt, my leadership style once again changed. I had the knowledge to make decisions and guide team members in a different manner- one that depended heavily on how much I involved myself. Thus, my main development point was in managing doing things myself versus delegating tasks to others to gradually develop their skill set over time. While the latter was typically the way to go, it was also pertinent to identify the kinds of tasks that may interfere with the production timeline or were too niche to justify someone else spending precious working time to learning about it before completing it.

There were also big rule changes in the mission itself. In addition to more tasks requiring more sophisticated equipment, there were now many more portions of the mission that involved crucial knowledge. On top of the existing requirements of biochemistry and spectroscopy for our own system, there were now requirements for geology and stratigraphy. These developments made it very difficult to onboard new team members in a manner in which they could assist in making decisions for what they worked on or how the robot looked. Instead, myself and the other leaders had to make crucial design decisions based on our own independent research into those fields prior to the beginning of the year. While necessary given the nature of our program and the abrupt changes in the rules, it was nonetheless difficult to get students motivated to put in the time for research before making prototypes.

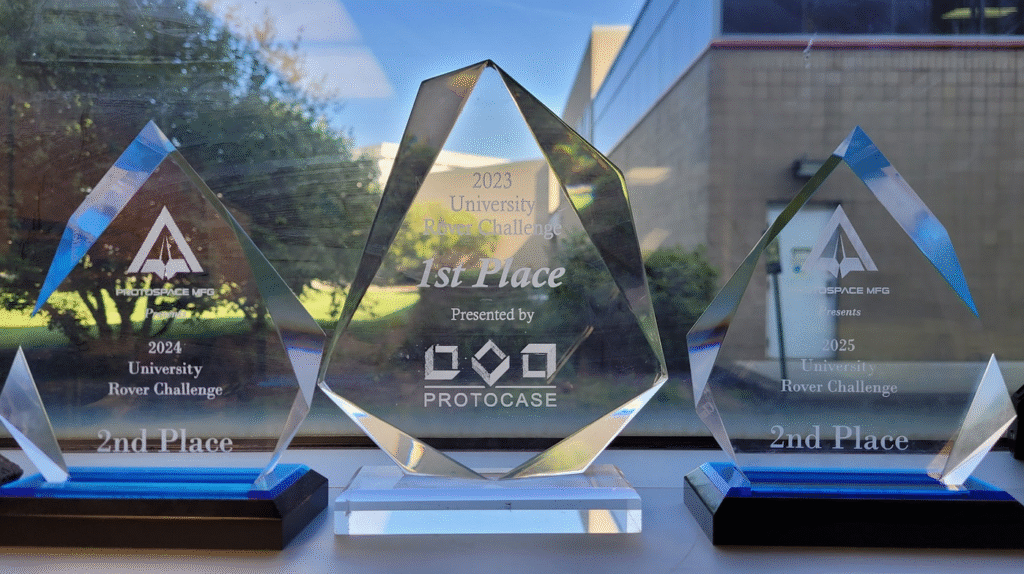

My Study Abroad experience cut my 2024 year short, so I didn’t end up going to Utah with the team. It also wasn’t until halfway into the 2025 year that I was able to come back. But, I didn’t leave before guiding the Science team to recreating the science payload and adding all the new functionality required; as a result, we scored in the top 5 for Science at the 2024 competition. Overall, the team placed 2nd.

Back for more

Coming into the latter half of the year after my Study Abroad, I picked up where my friend, Riley, left off after he graduated. There was no Science package and the video submission deadline was looming overhead. Over the course of five weeks, I led the small Science team to finalizing the design, fabricating, assembling, testing, and filming the payload- all in time for the video, for which I was the director.

Due to the tight time constraint preventing proper iteration and testing, I immediately switched gears after the video submission to have the team focus on maturing the designs. While some shortcomings could be fixed with movie magic for the video, Utah required a properly prepared system.

We were able to get a solid system ready in time for testing the full rover prior to Utah. While it had some hiccups here and there, it was more than capable of completing the entirety of the mission.

At competition, our rover did very well in every category. Even in one mission where we had a 10 second delay due to outside interference, we managed to score well above average. I was in charge of the Science mission

This was enough for another 2nd-place finish- solidly establishing the program as a consistent frontrunner in the ecosystem.

Since the competition wasn’t until the end of May, my own graduation felt more like a small break in the middle of URC season. Being in Utah felt odd, though. I knew it was my last competition; now that it’s over, it’s that same weird feeling coming back to Morgantown. Rather than a big event like graduation, the ‘feeling’ of being an undergraduate slowly dispersed, instead. That is, until the competition itself catalyzed the shift and I found myself on the road towards Morgantown from Pittsburgh’s airport being shed of that feeling and instead having another replace it. I’m not sure what that feeling is, but I think that’s the point. I believe I’m meant to define it myself going forward. URC followed me through university, and its completion marks the beginning of the next chapter.

Picture of the Science mission team. From left to right: Connor Mann, William (Bill) Streck, Elijah Motter (below), Izaak Whetsell (above), Jalen Beeman, and myself

Full team for Utah. Good pictures like this were difficult to get since we were standing in the hot desert in the middle of summer and the ground was reflecting the sunlight. We treated ourselves to appreciating the local National Parks after we finished all of our missions.